In 1999, 104 years after the Impressionist painter Edgar Degas used a camera to create forty or so photographs, they went on public display. Degas, we learn, saw these works as experiments and explorations of a medium new to the world in general, and to the artist in particular. He never showed them publicly and only a select, inner circle of friends, were permitted to see them. Contrast this to the fact that Degas was one of the primary forces and one of the best known painters who pioneered the creation of 19th century French revolution in art, called the Impressionist movement and whose shows attracted crowds from all over Europe.

The curated show of his private photographic works went to a variety of locations in Europe and America including the world renowned New York Metropolitan Museum of Art and the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles. The art Press and art historians were delighted to see something that had remained hidden about this French, 19th century giant, but was there a tendency to make more of the importance of this cache of concealed, private works, than is commensurate with their quality or volume? Is it the work of modern hype to attract attention or does Degas deserve to be called a photographer as well as a painter, sculptor, and print maker? Would he want this approbation himself? I think not.

From what historians tell us of his nature, his drive for perfection of his craft, his need for control of medium, his passion for the refinement of his art, he would not view a brief flirtation with photography as representing the level of mastery he required of himself in every other medium he chose to work in. Having said that though, there is something quite fascinating about his use of photography and the insights it may give us about how Degas experienced the world, what he pursued as an artist in his works and how his diminishing vision may have in the final analysis, made him a true Impressionist rather than the realist he preferred to be known as.

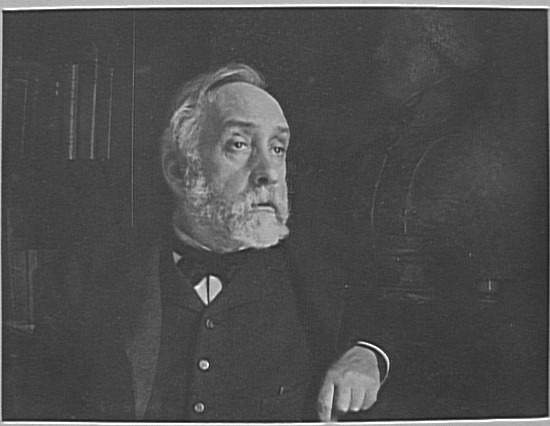

Edgar Degas was born on July 19, 1834. Named Hilaire-Germain-Edgarby his French father, Auguste, who was a banker, and his Mother, Célestine, an American from New Orleans, Degas was born at 8 rue Saint-Georges in Paris of affluent means. While family members in France and Naples had changed the family name “Degas” to “De Gas”, presumably sounding more aristocratic, Edgar returned to using the original spelling after 1870, in his late thirties. It was in this same manner of regard for tradition, that Degas began his art career in 1855, after abandoning his study of law. He enrolled at the École des beaux arts in Paris. Leaving Paris for Italy in the next year, he continued his artistic education by copying works from the school of Leonardo da Vinci. He returned to Paris five years later in 1861, and through his friend and painter Édouard Manet he met the group that would be known as the Impressionists. Degas was fierce about his individuality as a life philosophy and practice, and made efforts to avoid being labeled an Impressionist. Yet it was Degas who became one of the first of the group of renowned artists, to achieve recognition for this new art movement.

The period during which Degas worked was extraordinarily turbulent in Europe, especially for France, as it was the onset of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, the Commune insurrection in 1871. The Civil War that followed affected the country for decades. As art and artists are often the story tellers of a civilization’s decadence or cultural beneficence, we find in Edgar Degas’s work as a painter first and later for a brief year of his life when he used photography as a creative medium, an aristocrat who left a record of his own society’s indulgences, but who also found some form of comfort among the working class as their witness and interloper. His subject matter perhaps tells of what was, more than what was to become, making him revolutionary only in the right to paint how and what he wanted, but not in the sense of documenting the revolution of culture itself. Like the purpose of traditional portrait painting he had perfected, his less restrained work still acted as a photograph might in our day and age, to capture a moment in time.

Despite his radical approach to painting interpretively, Degas clung to the past in both his art content and his personal life. So it is interesting that his brief affair with photography, was highly exploratory, completely non-traditional and had he chosen to pursue the medium more seriously, or lived in the age of film making, he would have revealed something new about the creative process concerning the nuance of light and form or their absence, to tell story.

Between 1874 and 1886, the Impressionists exhibited their works in independent shows separate from the politically controlled salons. The term, Impressionist was introduced by the critic Louis Leroy, after viewing paintings in the first Impressionist exhibition in April of 1874. News reports of the time, as well as the majority of the French public, did not think the works by Monet, Renoir, or Edgar Degas as art that merited serious attention. Degas worked in many mediums, including oil, watercolor, chalk, pastel, pencil, etching, sculpture and briefly, photography. As an admirer of the old masters, particularly Renaissance painters, and the more contemporary works of Eugene Delacroix (1798-1863) and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), Degas copied works by earlier artists in the mid-1850s through the mid-1870s and created his own history paintings, portraits, and scenes of daily life. Later abandoning his history painting for more attention to portraiture, turning images of relatives and friends into complex psychological studies is a tendency seen again, in the collection of his photographic works.

His departure from traditional portraiture, to painting impressions of people, is replicated through the lens of the camera. When Edgar Degas turned to photography at the age of 61, his eyesight was failing, his sister was dying and so was the France he had come to know. Caught up in the fury a few years later of the anti-Semitic Dreyfus trial, Degas divorced some of his closest friends including the Halevy’s whose disembodied figures are a subject in his photographs. Some of the portraits are double exposed and seem to dislocate heads from the bodies of his friends. One of Elaine Halevy on the couch suggests something surreal; the body becomes more akin to a shape shifter, as in shamanistic traditions. This dance with spirits, as one might call it, may have been more than a passing fancy for the artist, and seems to go relatively unnoticed by commentators except for an article by author, Carol Armstrong and another by New York Times columnist, Michael Kimmelman whose Oct 16, 1998 article asks “Did Degas also look at spirit photographs of the time?” At the time he was taking his pictures, others around Europe, both authors point out, were taking what came to be called spirit photographs. People were making an attempt to photograph apparitions of the dead and other spiritual entities. They were attempting use this new technology to reveal what even the eye cannot see. Perhaps in the end, Degas felt photography was a little like cheating in the same way the curtain gets pulled back revealing the wizard of oz. Or, perhaps Degas found photography a step removed from his feeling nature, which with pen, brush, or pastel, is part of the artist’s breath, limb and even heartbeat. More of the artist is in the fine art work itself, than can be said of the artist’s presence in the photograph. In this way, Degas may have found the medium of photography too removed to be of value to his inner experience in the act of creating itself, but useful as a means for exploring subtler aspects of the visible world.

Using the word ‘Realist’ himself, to suggest a focus on real life and ordinary events, elevating the common place to the supreme, was how Degas wanted his work to be known. For the viewer then, was Degas a Realist for the meanings he intended, or an Impressionist as art historians have come to call his art, a movement he helped found and promote? Perhaps, like his paintings, sketches, and later photographic works, all of his work was ultimately an impression of reality. Less concerned with what things looked like, Degas is devoted to how they feel. It seems as though it is through his art that he engages his own deep feeling nature that perhaps personal relationships did not elicit.

Degas never married, but one can easily see that he had lifelong mistresses. They were the images he adored in dancers, milliners, and bathers. With the intimacy of a lover he reveled in their bodies, in their shape and movement, in the quality of shoulder, or back, a gesture, a wave of a skirt, a slight tilting of the head, a glance away from each other, a shift in light. It is said he delighted in the presence of his dancer models and others and yet was not prone to socializing.

In some sense he seems to have experienced some quality of relationship with the subjects of his works – which for the most part were living human beings. He painted dancers, horse jockeys, spectators, milliners and bathers. But in all cases, he was a witness, an on looker who then took back to his private studio his sketches, impressions and memory of what he saw, to reinterpret them as frozen time capsules. Like his penchant for solitude personally, his photography conceals the real and portrays the imaginable.

To show the extent though, to which Degas had come to rely on his art as his way of relating, speaking, being in the presence of the world, as if to say, “my art is who you can relate to, leave me out of it,” is a story about his ill sister. In 1895, the same year he created his unusual body of photographs, his beloved sister Marguerite was dying in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Degas decided to ship her a camera. As he explained to her then, it was “capable of both posed and instantaneous views.” With “no more than a month of practice,” she would be able to send him “a few good portraits”–including, he specified a few days later, “some negatives that I can have enlarged to see you better.”

Perhaps knowing he could not go to her, nor she and her husband come to him, he felt photographs unlike letters, could tell more with images than words. But here he hopes that his new found art technology, will preserve some thread of life between them; keep them in touch so to speak. More a soliloquy for a new age, than one passing, in this one way one could say in this isolated act, Degas becomes a photographer. He did not think to hire sketch artists or find some other means of communicating with his sister. This real medium, photography, that had the possibility of recreating an exact replica of the real three dimensional field before its lens, this he might have thought, can help preserve memory which was historically, a faculty he had highly developed. But his attitude about the medium somehow being less intimate than painting, might explain why his photographs tended, rather than towards realism, to abstraction. It seems that the reality of life as it is, is not of interest to Degas. He likes to poeticize images, or the relationships he captures, with hues, tones, and shapes whose edges do not forbid the viewer from entering. He seemed a captor to the desire for showing the world an inward feeling of an outer state. Degas’s photographs show us this affair with a subtle force, an effort to portray the energy and presence of something concealed. Like a secret, the content should only be suggested but not revealed entirely keeping something from the viewer, perhaps a piece of his own heart.

We see this in the fact that to his dying sister, he sent no loving letter, no consoling words; he sent her a camera as if to declare, “Send me an image of your self. I want only to relate to images.”

Degas related to images of life it seems, with a deeper love than was seen in many of his personal relations, other than his love for his mother and his blind cousin Estelle Masson, whom art historians say Degas may have had loved and had special compassion for, as though pitying his own future of dimmed sight.

When he experimented then, as an artist rather than a classical portrait photographer, we see a similar effort to make something more of the mundane than we might see with the naked eye. His photographs focused on capturing the spirit of a person or relationship rather than its concreteness. His painting of his cousin Estelle like his photographs of the Halevy couple, and others, could be called ghostly or spirit like. While some historians suggest he turned to photography to replace sketching, in 1897, one year after his photographic experiments, he returned to sketches which, while becoming less specific and more general, one sees in his matured talent, a more total feeling for his subject than his earlier sketches which displayed greater details. As a mature artist, Degas was able to show more with less. He seems to have become comfortable with the general feeling for something, rather than its particular parts.

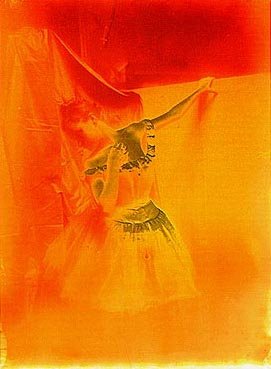

So it is of note that the photographs that made the world tour in 1999, show disembodied people who were his friends including the Halevy’s whom he later excommunicated from his life for the sin of being Jewish. We see a dancer who is more the skirt whirling than the limbs in motion. It is as though he is looking for what animates form, for how the light breathes into a subject, than he was the details of the subject. He was searching for the hidden light. He is not alone as a painter or a photographer in this pursuit, as in essence, both crafts are a relationship with light.

Spirit photography expresses this dichotomy between the seen and unseen most profoundly. Here one is trying to capture the invisible in a medium one cannot see until it’s processed chemically. In other words, we interface with the hidden all of the time but we are blind. Blindness we know enhances other faculties, and this shows itself in musicians who are gifted despite their blindness or perhaps because of it. Edgars own life long eyesight problems may have held the germinal cause of the way he painted, how he literally saw the world, which had blends of tones, hues, blended colors and shapes, suggesting things coming into being, rather than static images of things that already exist.

In the three glass plates of his photographs of dancers, Degas elicits wonder and curiosity, even awe for their vagueness, their abstract and gorgeous, almost oriental orange color. All three were studiously used and would later become particular and general in his paintings. The pose in each picture of his dancer’s, a favorite theme for Degas, were all taken in 1895, when they were given the names by which they are referred to today: Dancer (Arm Outstretched), Dancer (Adjusting Her Shoulder Strap) and Dancer (Adjusting Both Shoulder Straps).

Perhaps for Degas, photography was a new technology he hoped he could use to manipulate images the way his inner vision did, in his imagination. His works show an amazing capacity for capturing the spirit of a situation; even manufacturing them with bright lights that obliterate a person’s features, allowing shadow, the darker side of the subject to be highlighted.

Degas may have found in photography, something he lacked in either drawing or personal life – an image of an image – the possibility of creating how the artist experiences the interior nature of the subject in front of the lens. His photographs show us his desire to come into rapport with something more ethereal than physical, something more textural than smooth, something real but suggestive, like the spiritual dynamism in life, the interior composition, its energetic make up, more so than its outer form as a hard exterior reality.

In photography one can sees what is there, and can replicate a moment in time, holding for the future the feeling we had when the photograph was taken. But in Degas’ photographs there seems little focus on using the medium to replicate or even preserve life. Rather, the pictures I have been able to see reflect his ongoing fascination with what can best be termed the light of spiritual energy. One sees this in the dramatic photograph of the whirling dancer whose fluttering dress in stark shades of black and white, offer us a sense of the grey that happens only in movement. His abstract plates of the three dancers capture something even more ephemeral, the etheric that is bound to the physical, the feeling of the physical as we engage it. While considering himself a Realist, his photography was distinctly Impressionistic. As his photographic prints did less to capture what something looked like in real life, rather, they captured the artist’s imaginal experience of what he saw.

His photographs seem like the conjuring of inner landscapes, perhaps explaining his dissatisfaction with painting real ones much of his life. Rather than perpetuate idealized images of mythological figures and historical subjects, he wanted to paint everyday urban scenes. Degas needed to elevate the mundane to something spiritual and beautiful. Yet, as a private man, he was prone to recluscivity. This gives us hints as to why, when photography became a possible art medium, Degas was eager to experiment with it.

A photographer is given permission to stare at others without interacting with the subjects of his lens other than through vision itself. It is a solitary exercise of observation giving the photographer a certain control in the relationship. But unlike today’s cameras, the cameras of Degas’s day did not have the control over the amount of light that enters the lens the way his brush and paint could on the canvas. This was his medium.

What we do see though in Degas’s experiments with photography, was the capacity to explore a medium, as a mean of communicating something mysterious about living and life. Perhaps like the séances of his time, his painting and sketching were his medium through whom other worlds spoke. Might this explain why his photographs, like the intimate letters from his cousin which he kept privately, were not meant for public viewing but rather were to be understood as a deeply personal attempt to find something his eyes were soon to loose, something between the artist and his art that like his mother, and his sister, was passing away?

His photographs of dancers and friends, a woman drying her self, and others, show a distinct retreat from particulars to the more ephemeral sense of the overall essence of his subjects. It is as though he became more intimate through feeling, as his eyesight dimmed over the course of his life, and his hearing weakened. With limited senses, he had access only to the impressions of things. So, though Degas had hoped to be known as a Realist for depicting real life scenes, in fact it was at the end of his life’s work, that he seems to have reached some sort of peace with his inner quest for feeling, through the act of creating lasting impressions of life itself. In this way one could say his several dozen photographs leave us with a lasting impression of Degas’ inner experience as an artist, and that they are private meditations more than being the works of a professional photographer, which he makes clear by abandoning the medium, only a year or so after his initial experiments.